Hysterically normal

When we hear the term “hysteria” in everyday language, we grasp its double-edged meaning from its past, cumulative contexts. On the one hand, hysteria is associated with women or feminine persons, thus gendered; on the other hand, it is used in semantic contexts to mean irrational, exaggerated, or theatrical. Thus, the term is used not only pejoratively but also in a reactive way, for example, when in polemical discourses groups or individuals that point out grievances or highlight dangers are called "hysterical". When the term hysteria is applied to a person who is neither female nor feminine-performing, this intends to denigrate them through an implicit feminization.

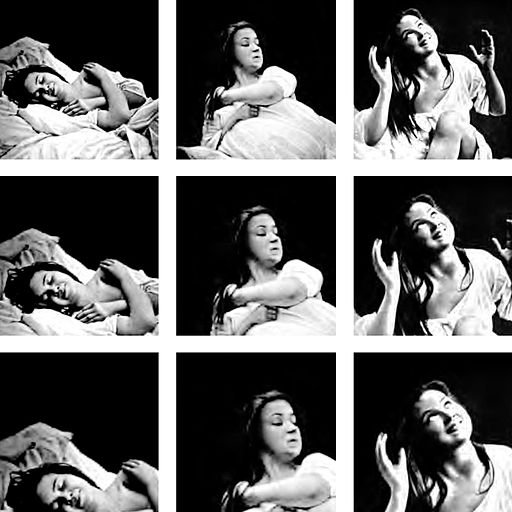

Drawings of a woman in catalepsy (Albert Londe, 1893)

A brief historical review of a constructed female disease

From the very beginning, hysteria – derived from “hystera,” the Greek word for uterus – has been linked to the biologically and psychologically feminine. Already in ancient Egypt, the idea of the wandering uterus arose as an explanation for behavioral anomalies in women. The uterus could “dehydrate”, become detached, and wander in the body, causing blockages there. Galenus, a physician active in the second century A.D. whose ideas influenced medicine until the 17th century, believed that hysteria was caused by an unsatisfactory sex life and that nuns, virgins, widows, and women with bad husbands would suffer particularly. For relief, massages of the pelvic area performed by midwives were recommended. Avicenna (980–1037) – a physician in the Arab world – also described female suffering that was caused by a lack of female satisfaction and could be cured through orgasms, which could be produced by doctors or husbands through manual therapies (Grose, 2016).

Conditions that would have been attributed to hysteria at other times were handled in the Middle Ages primarily within the domestic sphere. For patients with different mental illnesses, public institutions supported by charity or taxes were established – in addition to the notorious “fools' cages”. In the more recent modern period (ca.1500 to 1789), the confluence of plague, reformation, extreme weather events, and political unrest provided a breeding ground for the emerging witch hunts. Under these influences, hysteria became associated with sin and eventually even with demonic possession. Through the Enlightenment, hysteria was given the status of a medical diagnosis, an improvement that could clear women of the suspicion of witchcraft (Arnaud, 2015).

After the French Revolution, Philippe Pinel, founder of scientific psychiatry, reformed the asylums, which at the time resembled penitentiaries. According to legend, he freed inmates from actual and metaphorical chains and regarded them as sick people who could be cured and deserved humane treatment. This paradigm shift occurred in different parts of Europe. Yet even within this progressive development, the gendering of hysteria was perpetuated.

In a century marked by the creation of categories, physicians construed hysteria as a disease particularly difficult to define (Arnaud 2015), a medical catch-all term for all sorts of hard-to-define symptoms such as insomnia, disobedience, lack of desire, but also an excess thereof, as well as epilepsy or such mental disorders that are now classified as dissociative. Men with similar symptoms had initially been diagnosed differently from women, as the term hysteria had a female connotation. It was not until, in the second half of the 19th-century, the neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot located the cause of the disease not in the uterus but the nervous system, thus making it possible to diagnose hysteria in men. He noted, however, that in men a traumatising incident, such as a violent event or a work-related accident, was the origin (Mitchell, 2000). In women, the cause of illness must be innate, since the female temperament is hysterical at its root, as the physician Auguste Fabre wrote in 1883 (cited in Showalter, 1993).

A dramatic reproduction

Jean-Martin Charcot's domain was the Hôpital de la Salpêtrière, where he modernised neurology through his clinical and pathological descriptions.

He is best known to laypersons today for his study of hysteria, but this aspect of his research is also retrospectively viewed most critically. Charcot gave weekly teaching lectures in which he presented his findings effectively to the public. He demonstrated his theory on the treatment of hysteria under hypnosis in the amphitheatre of the institute, preferably using his patient Marie (Blanche) Wittman. One of these lectures with Wittman as the subject of the presentation was immortalised in 1887 in the painting Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière. Charcot employed photography as an innovative and truth-telling medium to document and publish his research. In 1877/78, Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière was published: photographs of female patients, taken by Paul Regnard, illustrated the descriptions of Charcot's research on hysterical-epileptic seizures.

Excerpt from Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière (Jean Martin Charcot, 1878)

The photogenic Augustine Gleizes, whose expressions of hysteria were considered particularly vivid, appeared particularly frequently in it. ”An extraordinary complicity between patients and doctors” developed (Didi-Huberman 2003), in which suggestion and performance determined each other within a power structure. Both Wittman and Gleizes came from poor backgrounds and were victims of abuse before being institutionalised at the Salpêtrière. After Charcot's death, Blanche reportedly exhibited none of the symptoms of hysteria. Augustine refused to be photographed much earlier and was subsequently kept in isolation until she eventually fled the hospital – but her likeness remained.

In 1928, the Surrealists celebrated in their journal La Révolution surréaliste the fiftieth anniversary of hysteria, “the greatest poetic discovery of the late nineteenth century, and at a time when the dismemberment of the concept of hysteria seems already complete.” Half a century after their publication, Regnard's photographs of Augustine in attitudes of passion (“attitudes passionelles”) promised the visualisation of an uncontrolled unconscious. Augustine embodied hysteria as the “most sublime form of expression” which transcends our moral world in favour of a desire for mutual seduction (Aragon & Breton, 1928).

Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière, André Brouillet, 1887

In Vienna, Charcot's research led to a different path. Between 1880 and 1882, the physician Joseph Breuer treated a young woman named Bertha Pappenheim for various physical and psychological symptoms. Breuer noted that Pappenheim lacked ”spiritual nourishment” given her "poetic and imaginative talent, controlled by a very sharp and critical mind," furthermore that she "led a highly monotonous life in her puritanically minded family, which she embellished in a manner that was probably decisive for her illness. She systematically cultivated waking dreams, which she called her ‘private theatre’” (Breuer, 1895).

In addition to medication, Breuer had his patient simply talk and associate freely. Pappenheim felt brief relief and called this (in English) her "talking cure." Using his treatment notes, Breuer and his young colleague Sigmund Freud developed their own theory of hysteria, which later gave rise to psychoanalysis. While Charcot, the observer, used the body and images as a means of diagnosis, for Breuer and Freud, language emerged as both a means of analysis and a therapeutic device.

In recent decades, cultural studies and feminist scholarship into science and history have critically examined hysteria in a breadth that I cannot adequately do justice to here. The diagnosis “hysteria” is no longer medically sound because it is inaccurate, and the feminization of the term is regarded as problematic. Areas of the diagnosis are now covered by the term “histrionic personality disorder,” which, however, is also assigned characteristics considered typically feminine: melodramatic behaviour, emotional lability, active dependency tendencies, overexcitability, egocentrism, a general seductive behaviour not directed at a specific person, suggestibility – and also includes an excessive preoccupation with appearing outwardly attractive (Sulz, 2010). The word histrionic stems from the Etruscan word for actor and implies both the attraction and pathologizing that these tendencies entail.

I’ll tell ’em what I like, what I want, and what I don’t

But every time I do, I stand correctedBritney Spears, Overprotected, 2021

The story of Pinel as the liberator of the “insane” (alienés) was immortalized in 1876 by the historical painter Tony Robert-Fleury in a painting that still hangs in the Salpêtrière hospital. It shows the fictitious scene in which the doctor orders the metal shackles of the inmates of the Salpêtrière to be removed. The older women are staged as extras at the edges of the picture, grotesque, clearly marked by life but at the same time infantile: one wears oversized bows, another holds a doll. Brightly lit are three younger women. The first one, in the center of the picture, is about to have her handcuffs removed and stands entranced and embarrassed as if she is being asked to dance. An angry woman, still handcuffed, her blouse slipped provocatively, kneels. The third, slightly in the background, is writhing on the floor, her right breast fully exposed.

Tony Robert-Fleury: Pinel, médecin en chef de la Salpêtrière en 1795, 1876

These fragments recall paparazzi photos of young female celebrities in various states of excess, addictive behaviour, and even despair. In the 2000s, gossip blogs, both professional and community-based, fueled the dissemination of these exploitative images. In a culture that encourages young women to stage themselves attractively – and alternatively rewards or punishes them for doing so – women in the public eye serve(d) as fuel for our fascination with the histrionic. The documentary Framing Britney Spears (2021) recounts Spears' career up to the point where she, as an enormously successful singer and mother, is under the conservatorship of her father, through an overview of its reception in the media. The strange, legal-financial construct appears to parallel the women who, two centuries ago, were institutionalised by fathers or husbands if they behaved in ways the latter deemed socially unbecoming. As a female pop star, Spears had to navigate the conflicting roles she embodied and her private identity for all to see. The documentary addresses the images of Spears defending herself against the harassment of paparazzi in a crisis situation – but not our stake as onlookers, as consumers, in the perpetuation of these narratives about women.

The history of hysteria teaches us to rethink the idea of illness as an abnormality and instead reflect on our mutable conditions. Mental health problems need to be destigmatized by normalising the conversation around these issues and taking them seriously. At the same time, we should ask ourselves why it is supposedly female behaviours and characteristics that are assumed, celebrated, and medicalized – under the subtle control of a societal disciplinary power that operates through media and individuals.

Bibliography

Aragon, L., & Breton, A. (1928, March 15). Le cinquantenaire de l'hystérie (1878-1928). La Révolution surréaliste, n°11, S. 20-22.

Arnaud, S. (2015). On hysteria: The invention of a medical category between 1670 and 1820. The University of Chicago Press.

Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1895). Studien über Hysterie. Franz Deuticke.

Didi-Huberman, G. (2003). Invention of Hysteria. Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière. Translated by Alisa Hartz. The MIT Press.

Grose, A. (2016). Reclaiming hysteria. In A. Grose (Ed.), Hysteria today (pp. xv-xxxi). Karnac Books.

Mitchell, J. (2000). Mad Men and Medusas. Reclaiming Hysteria. Basic Books.

Showalter, E. (1993). Hysteria, Feminism, and Gender. In S. L. Gilman, H. King, R. Porter, G. S. Rousseau, E. Showalter. Hysteria Beyond Freud (pp. 286–336). University of California Press.

Sulz, S. (2010). Hysterie I: Histrionische Persönlichkeitsstörung. Nervenarzt 81, 879–888.

Further recommended reading

von Braun, C. (2009). Nicht ich. Logik Lüge Libido. Aufbau.

Doyle, J. E. S. (2016). Trainwreck: The women we love to hate, mock, and fear… and why. Melville House.