Radical climate protests: Stories of success or failure?

Across Europe, radical climate activism is on the rise. Climate activists organise sit-in blockades, glue themselves to streets and oil plants, or create activist art events. They all have one thing in common: They want to end the fossil fuel status quo and force politicians to act, but, usually, their actions lead to nothing but criticism and public outrage. But is their protest pointless?

© Viola Karsten

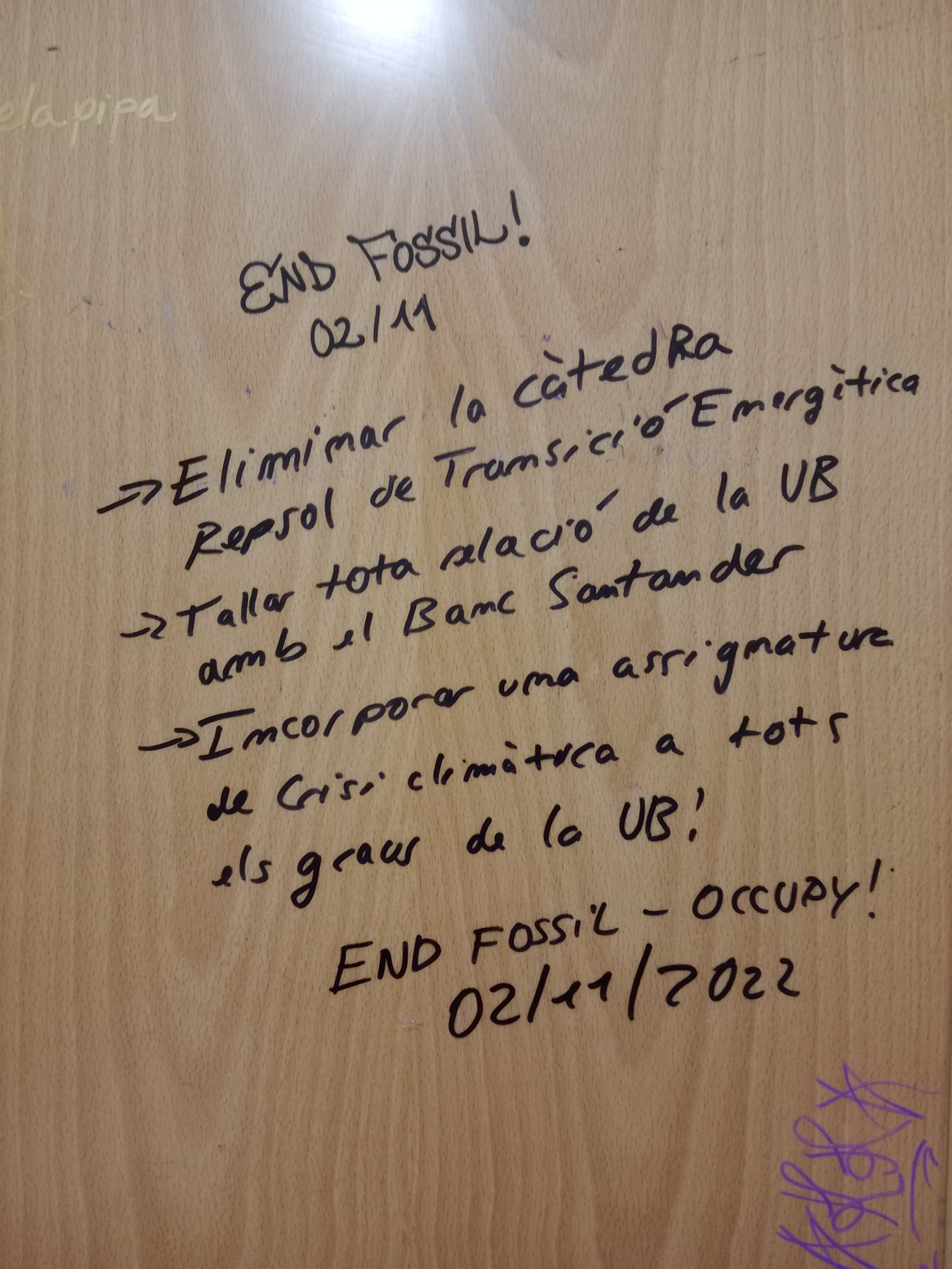

It is cloudy on this mid-November day in Barcelona as Elena and her fellow students make their way to the main building of the University of Barcelona. In their arms, they hold tents, sleeping mats and other camping equipment: They need them for their plan to camp in the university until their demands are heard. These were simple: The University of Barcelona should cut all ties with companies and banks that invest in fossil fuels and a mandatory course on the social and environmental impacts of climate change should be introduced for all students.

A week and numerous negotiations between students and the university's presidency later, the university agreed to the mandatory climate course and, under renewed pressure from climate activists, also loosened its ties with oil and gas giant Repsol - a major success for the movement.

The success of this End Fossil action comes amid a wave of radical climate actions that have recently driven a surge in media attention all over Europe. Groups called "End Fossil”, "Last Generation”, and "Extinction Rebellion’’ are using new, sometimes more radical tactics to try and force governments to act on the climate crisis.

But, unlike the case in Barcelona, many actions did not yet deliver instant results.

Two months before the Barcelona occupation, in the Dutch province of Drenthe, 55-year-old Dutch activist Conny Darwinkel and the rest of the local Extinction Rebellion made their way to the square in front of the main entrance of the Drents Museum. There they staged an art performance and handed out leaflets to bystanders, criticising the museum for its continued collaboration with NAM, a joint venture between oil companies Shell and ExxonMobil. The company is responsible for gas extraction in the region, which causes severe environmental, financial and emotional damage. Until today, the protest has not ended the financial friendship between the museum and NAM.

© Extinction Rebellion

© Extinction Rebellion

About 700 km southwest of Drenthe, in the German city of Cottbus, activist Ava (name changed) and her companions decided to act even more drastically. Together with 40 other activists, she blocked a power plant that was supposed to be closed due to its high water usage and droughts in the region but was left open in the wake of the energy crisis. Chained to the coal mine’s conveyor belts, Ava’s friends made video statements pointing to other sources of clean energy, arguing that, because of the power plant's water consumption, it was not worth keeping open.

As a result of the protest, Ava spent three months in jail. Not only that, but her protest was severely criticised in the media. The country's interior minister made a public statement demanding that the “climate extremists” be taken out of business. Even a local politician from the left-wing party in Cottbus didn’t think that the “form” of the action was chosen wisely.

Jänschwalde coal mine in Cottbus, Germany © Philipp Czampiel

But does that mean that Ava’s time spent in jail was not worth anything? Or that Extinction Rebellion simply failed with their creative protests in Drenthe? What is the point of radical climate activism if instant results are not achieved?

Does climate activism work?

Washington State University sociologist Dylan Bugden asked himself a similar question: Does climate activism work? In his peer-reviewed research, he found that it works under certain circumstances. By increasing public support, climate protesters can change public opinion, turn bystanders into participants in the movement, and put pressure on policymakers. Bugden’s study offers evidence that climate protest is facilitating precisely this form of social change. Thus, climate protests may make non-mobilised observers more likely to join in the action, and this, in turn, may even have an effect on carbon emissions. While Bugden might not have investigated this new wave of radical climate protests specifically, his findings might hold true for radical climate action as well.

After the recent national Extinction Rebellion protest in the Netherlands, media coverage surged drastically. As a result, activist Conny Darwinkel noticed the media finally started to show interest in local climate protests, which was new for her. At the same time, her fellow activists say membership has increased in their local Extinction Rebellion chapters.

Extinction Rebellion NL protest on January 23, 2023 with over a thousand people © Viola Karsten

Darwinkel, therefore, does not even question whether their specific protest in front of the museum in Drenthe was successful. Basically, the actions of Extinction Rebellion Drenthe should be seen as part of a “whole”, she says: “a mission that chafes (or nags) until the museum gives in”. Their group has many more protests in the proverbial pipeline to "influence public opinion" and create awareness. They do not seem in a rush.

Professor of Psychology Lauren Duncan from Smith College University also agrees with the need for a certain kind of patience in activism: “You know, protests or activism will be going on for a long time, and then suddenly there'll be a tipping point, and then that will be it. [...] Honestly, a lot of it is about timing, being at the right place at the right time with the right action.”

Gay marriage in the United States, she says, is a prominent example. Once unheard of, after years of protest, it is now inconceivable to many US-Americans that there was once a time when gay relationships were a crime.

Even in Cottbus, Germany, Ava does not seem shaken when confronted with the fact that her protest was not successful. After all, the goal was never really to shut down the power plant, she says. This protest, she says, was part of a larger strategy to make the region less dependent on coal in the long term - this could take years, according to Ava. Their role as radical activists, she says, was to create disruption and, through that, attention in the media and among the citizens of Cottbus. Thus, she says, her protest could give the moderate local environmental NGOs a boost to enter into negotiations. The NGO had long been calling for the power plant to be stopped, but had however never received a lot of media attention for their cause – now, according to Ava, negotiations became more likely to happen.

Radical protests give more legitimacy to moderate action

In science, this tendency can be explained by the "Radical Flank Theory". A term coined by Herbert H. Haines in 1984. Haines noted that funding for moderate black organisations increased rather than decreased with the rise of the radical black movement. Similarly, Dutch behaviour scientist Reint Jan Renes argues in an interview with the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant that this can be applied to the Climate Movement. "The soup throwers are basically frontier soldiers who, against themselves (because of taunting and social exclusion by society), create a situation in which others get the chance to put into work the necessary change", Renes says. Could it be that, in fact, other groups calling for the coal phase-out in Cottbus are able to arouse sympathy unlike Ava and her friends? And does this effect also apply to a cross-border climate movement - could actions like those of Ava and the other activists give people like Conny Darwinkel in Drenthe more legitimacy for their actions?

The fact that local politicians made degrading remarks about her protest is not a problem for Ava. “It was never our goal to be popular”, she says. According to her, simply the fact that they got politicians to speak out makes a difference. Flemish sociologist Ruud Wouters can confirm Ava’s theory. In an interview with Tilburg University, he noted that forcing politicians to take a stance sparks social debate and provides clarity in an electoral campaign, especially at the local level. Wouters indicates: “Protest forces political parties to take a clear stand. In fact, protest is a challenge to other actors in society: Are you with us or against us?”

© Viola Karsten

Opinions and strategies differ - but there’s one goal in the end

Yet again others, such as Andreas Malm, author of the book on radical activism “How to Blow up a Pipeline”, believe that symbolic forms of protest, performed by the protesters who threw tomato soup at Van Gogh's sunflowers at the National Gallery in London, do not go far enough. In a recent Guardian article, Malm was quoted saying that by making an absolute commitment to non-violent civil disobedience, fossil capital no longer has anything to fear from public opinion in bourgeois states where “capitalist property has the status of the ultimate sacred realm”.

However, other studies point to the impact that protest, in whatever form, can have at the local level. A recent study by German scientist Lennart Schürmann found that protest events in the electoral district positively affect the MP's (German Members of Parliaments) attention to the Climate Strike Movement on Facebook and in parliamentary debates. Another recent study by the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich found that the local strength of the climate movement led to more votes for the Greens in state and federal elections in 2019 and afterward.

In the climate movement, strategies differ. But whether a group is achieving tangible results, sees art protests as part of a larger strategy, or even directly tries to disrupt fossil flows, what they have in common is that they are pursuing a bigger plan. And, despite their success in Barcelona, Spain, Elena and the other activists will not cease their protests - they want more. Currently, they are mobilising other students to occupy universities and schools, with further plans by the Barcelona branch to organise more demonstrations. “Social movements need victories in order to galvanise their struggles, this was a relatively big one, at least big enough to revitalise parts of the climate justice movement”, one student says. And Elena adds: “Now we will scale up and demand things from the government.” For climate activists, there seems to be more to the idea of success than meets the eye.

Literature

De Volkskrant. (October 26, 2022). Tomatensoep en aardappelpuree op doek: hoe effectief is de nieuwste techniek van klimaatactivisten? Retrieved from https://www.volkskrant.nl/a-b2bac66d

Fabel, M., Flückiger, M., Ludwig, M., Waldinger, M., Wichert, S., & Rainer, H. (2022). The Power of Youth: Political Impacts of the "Fridays for Future" Movement. CESifo Working Paper No. 9742 Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4106055

The Guardian (2023). Climate diplomacy is hopeless, says author of How to Blow Up a Pipeline. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/apr/21/climate-diplomacy-is-hopeless-says-author-of-how-to-blow-up-a-pipeline-andreas-malm?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

Tillburg university news. (March 13, 2023). Are you for or against us? The impact of protest on political programs. Retrieved from https://www.tilburguniversity.edu/current/news/more-news/are-you-or-against-us-impact-protest-political-programs

Bugden, D. (2020). Does Climate Protest Work? Partisanship, Protest, and Sentiment Pools. Socius, 6. Retrieved from

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2378023120925949

Satell, G. & Popovic, S. (January 27, 2017). How Protests Become Successful Social Movements. Harvard Buisness Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2017/01/how-protests-become-successful-social-movements

Simpson B., Willer R., Feinberg, M. (July, 2022). Radical flanks of social movements can increase support for moderate factions. PNAS Nexus, Volume 1, Issue 3, pgac110. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac110

& further readings

Ortiz, I., Burke, S., Berrada, M., & Saenz Cortés, H. (2022). World protests: A study of key protest issues in the 21st century (p. 185). Springer Nature. Retrieved from https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/usa/19020.pdf

Haines, H.H. (October, 1984). "Black Radicalization and the Funding of Civil Rights: 1957-1970" (PDF). Social Problems. 32 (1): 31–43. Retrieved from doi:10.2307/800260. JSTOR 800260.