Dye for fashion

– Interview with Sophie Nelissen und Maike Vierkötter

The textile industry is one of the largest, fastest producing and most polluting industries on the planet. We are drowning in clothes and textiles. But are there also positive trends in the industry? TEMA spoke with Sophie Nelissen and Maike Vierkötter, who are both concerned with these issues on a daily basis, yet from different perspectives.

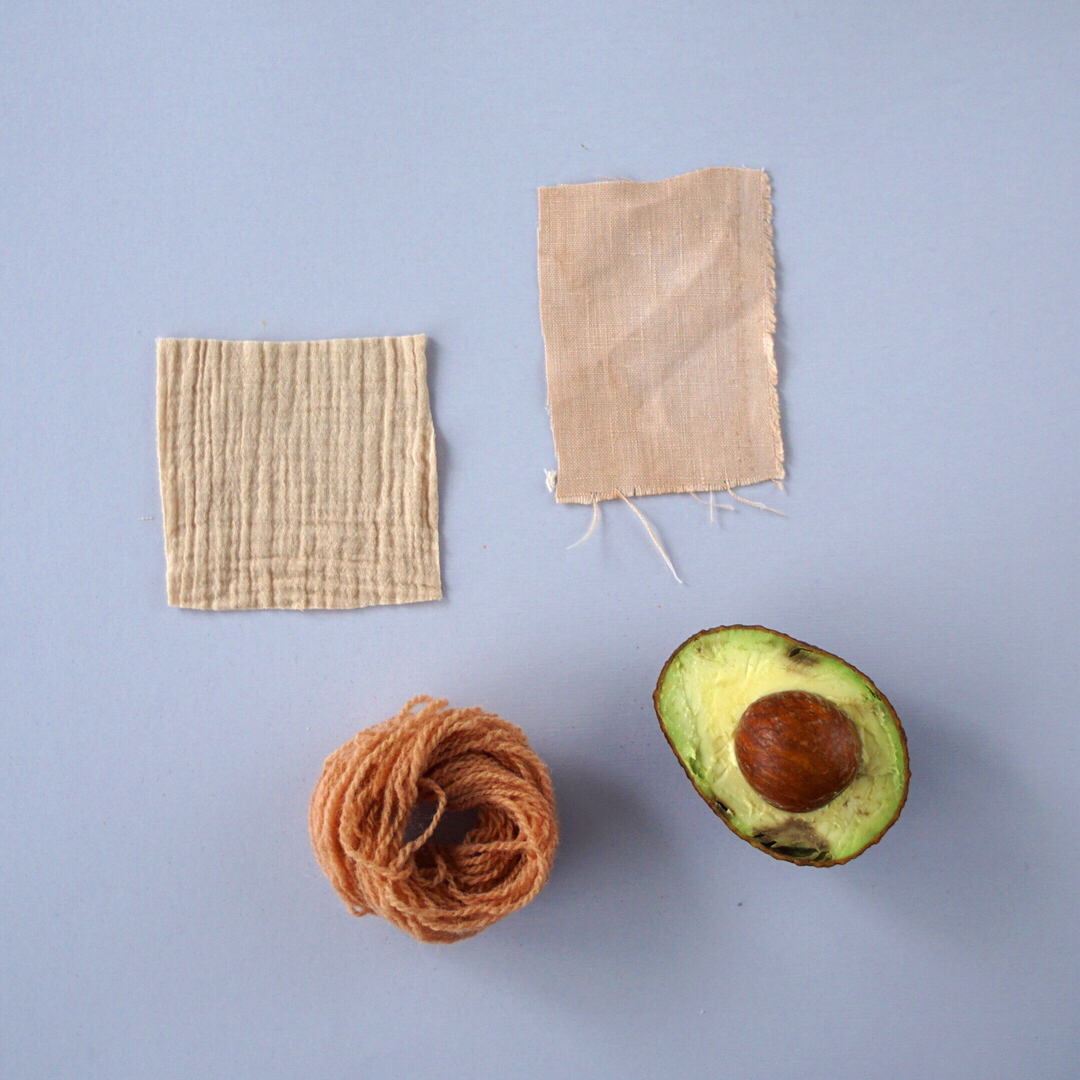

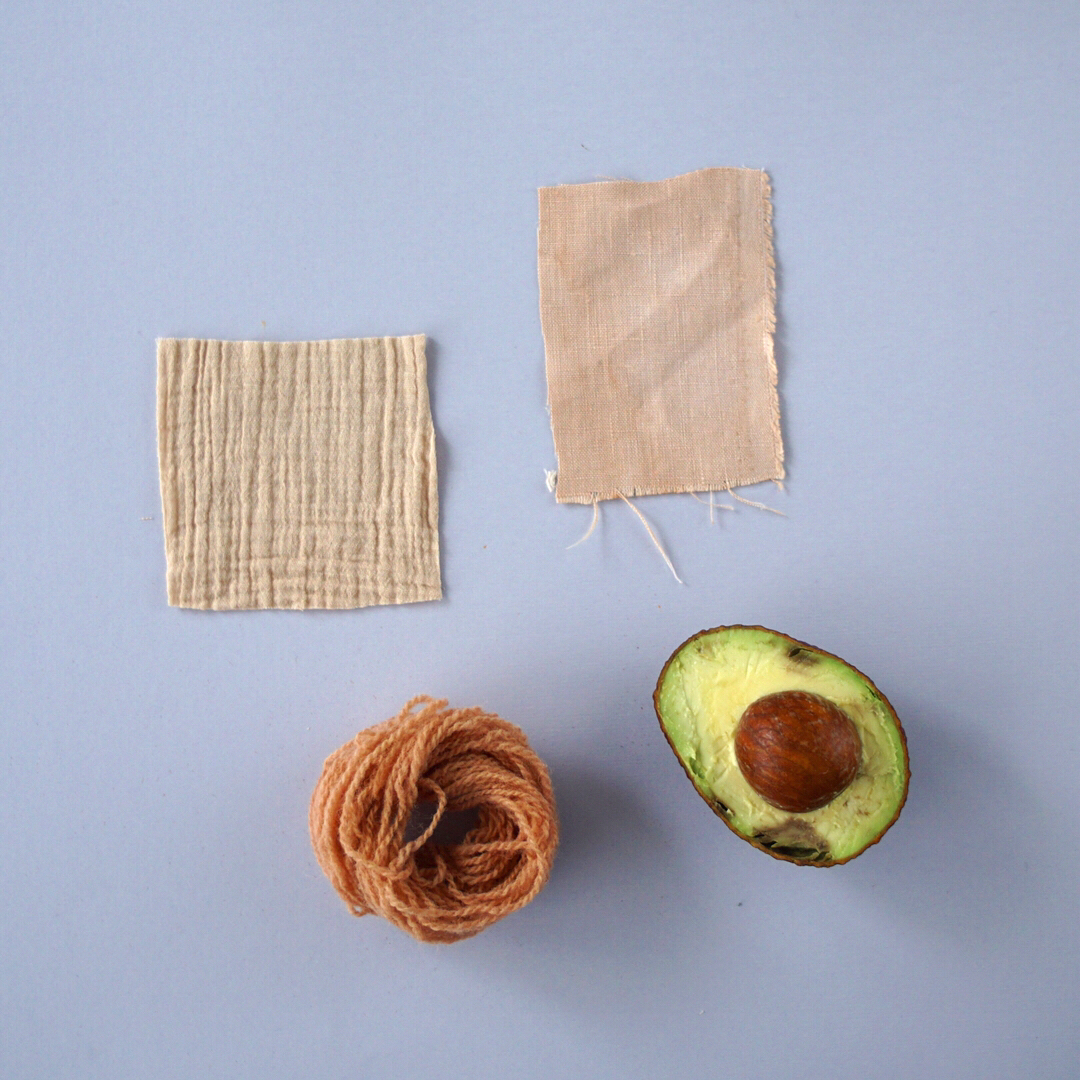

Sophie just started a small sustainable fashion label in Maastricht, Netherlands. Designing, sewing and dyeing the garments herself – also with plants she grows in her backyard, Studio Sufi was born out of the desire for a more responsible way of producing fashion.

With a love for fashion but an awareness for the destructive impact of the industry, Maike is currently in the course of graduating from her Master’s in Textile Industry and Applied Sustainability, while already applying her knowledge during her job in Sustainability Management, where she tries to push the issue of sustainability in fashion on a corporate level. For her thesis she recently produced a zero-waste beach-bag, together with the clothing brand SALZWASSER, where she oversaw every step of production while keeping an eye on the impact on both people and the environment.

Together we talked about conscious fashion consumption, the loss of craftsmanship and approaching the production of garments from a more holistic perspective.

©lauraknipsael

Viola: Sophie, your production circle looks very different from fast fashion and craftsmanship plays a big part in that. Could you tell us something about that?

Sophie: The craftsmanship that I am most interested in is the dyeing. I coincidentally met this girl who is really into becoming a shepherd. Her dream is to eventually have her own herd of sheep in natural reserves. And via her I got my hands on a little bit of wool that I would like to use to produce some socks, made in the Netherlands with Dutch wool and dyed with natural dye that I grow myself, so that it is a fully local and natural production circle. But then the tricky part is having it knit, because in the Netherlands it has been really hard to find people who manufacture socks themselves. And the next option, to have people hand-knit it, is not feasible.

When you are producing small scale, as I am, you notice that one of the reasons why producing small scale here is expensive, is because production cycles have been industrialised to a maximum, which requires big quantities unless you turn to small handwork. And as hourly wages here are generally more expensive, products become almost unaffordable if they are handmade.

“There is definitely the risk that we make the system a tiny bit better and then we feel good about maintaining a better version of the status quo.”

V: It is no secret that the fashion industry is facing a lot of problems, like this tension between market pressure and the need for socially and environmentally sustainably produced items. Maike have you also witnessed some positive trends in the industry as well?

Maike: I believe that the great awareness for high-quality and sustainably produced clothing is gradually coming back. This also comes with the growing awareness of climate change. And companies are responding to that. Of course, there are also various smaller labels, such as Armedangles, which has now been around for almost 12 years, which prove that you can survive as a 'sustainable' company, also in the long term. Of course you can ask yourself if what they do is enough, but in any case it proves that it can work. Companies are getting more courageous in putting sustainability on their agenda, to pay better wages and to use certified materials. But I think it's a combination of consumers demanding it, companies daring to offer it, and brave, smaller startups showing that it works.

V: I always struggle to distinguish honest and maybe radical aims from greenwashing. Big companies like H&M put ‘Consciousness’ lines on the market but at the same time still release 12-16 new collections per year. So how sincere and positive are these shifts in the strategies of bigger fashion companies really?

S: When conventional labels add natural dyed or organic t-shirts into their collection, or fast fashion brands make conscious collections it gives you the feeling like it's ok to keep consuming as we do. There is definitely the risk that we make the system a tiny bit better and then we feel good about maintaining a better version of the status quo. When we zoom out and look at the rate in which we are crossing planetary boundaries on all levels, we realise that we cannot maintain the status quo at all. So yes, you can say this is a positive development, because this is also the rate at which we as humans tend to innovate, and it will eventually get better. But, sometimes I think I shouldn’t make clothes at all because we have enough already. But we also have to keep faith. By taking little steps it is easier to keep courage.

M: I agree completely with Sophie. If I am completely honest, even with SALZWASSER, we produced a new consumer product the world does not need. But it offers an alternative to fast-fashion. Personally, it is very important to me that I do not judge anyone who goes shopping at H&M or Primark for financial reasons. This is totally understandable in this consumer society in which we live, where so much is about superficialities and appearances, that you want to keep up. But if there are people who can and want to spend 40, 50, 60 euros for a branded shirt, it is important to create awareness amongst them and to offer an alternative through a brand that tells a story.

S: With branded clothes, often the consumer assumes this is an expensive product so it must be made in a good way, but that is not always the case. It would be great if consumers in this price range come to understand that.

“It’s this link to the natural resources but also this way of being connected to the soil, to the earth, that is a very direct way to make a positive impact on the planet. “

V: What kind of techniques do we need, other than, as you mentioned, storytelling, to make consumers more conscious and influence their buying decisions?

M: I believe that you can achieve a lot through education. At some universities, there is this concept “Studium Generale” in which everyone in the first semester is introduced to different aspects of sustainability. In different stages and forms of education, like high school or vocational training, you become aware of the effects of your behaviour.

When I studied textile technology, sustainability was never a topic. As a result, we founded an initiative to implement this topic more in teaching. To train the people who are the next generation to work in this industry. To make them aware and say: "Hey, look, when you're dyeing something, there are an insane amount of chemicals in use." This realisation alone would be enough for me.

V: Sophie, you came up with very specific ways of tackling the problems that come with the conventional way of dyeing. How did that come about?

S: At some point in my research I became fascinated with natural dyes. The lockdown last year gave me a lot of time to work in my garden. But of course the colours are different. Especially on cellulose-based fibre, like cotton and linen, the colours are much lighter. But for instance on wool and silk you get very bright, shiny, beautiful colours. One of the reasons why I like it so much is this direct link with natural resources. In the same way like, for example, a traditional willow basket weaver uses the willow of their garden to weave a basket. You get very close to the origin of the product. Later on, I started learning about new ways of doing agriculture and then I realised that if you start planting in a better way, you actually start storing more carbon in the soil. It’s this link to the natural resources but also this way of being connected to the soil, to the earth, that is a very direct way to make a positive impact on the planet.

V: We spoke about change on a bigger level, that change on the level of production needs to take place but change on the level of consumer behaviour needs to happen as well. Maike, part of your job in the sustainability management team at the German bag manufacturer FOND OF is to speak to different stakeholders, trying to balance the size of the company and their commercial interests, with the sustainability goals you have set. Are there any problems you often come across by trying to balance these interests?

M: The company, and they admit as much, is not a sustainable company. FONT OF says we want to make good products, we want to grow and be as sustainable as possible. With three people in my team, in a company with 300 employees, we are quite well positioned. But it is not self-evident that there is a budget set aside for this. For example, in the past we were allowed to produce a cradle-to-cradle backpack (Note author: A design concept and certificate which makes a positive impact on people and the planet, without producing any waste). The work of sustainability management is very valuable, because they always initiate these thoughts but it takes an incredibly long breath to really get things moving.

“My dream would be that people become more aware about what is behind these products and then make conscious consumption decisions.”

V: But can big fashion and textile companies even be ‘sustainable’?

M: If they really want to, yes. But the other big question is, do we want to consume more at all? If you say we consume, particularly fast fashion, too much anyway, then even if we would take 100% recycled materials and use 100% natural colouring, it is too much.

S: I think your point of overconsumption is true. This goes back again to the discussion about to which extent we want to challenge the status quo. It is very difficult to make radical changes.

V: For radical changes, if you had a dream for the fashion industry and consumption for the future, what would it be?

M: I like fashion. I like that you can express something with it. My dream would be that people become more aware about what is behind these products and then make conscious consumption decisions.

S: Building on that, if everyone would have this kind of consciousness, we would have a different way of interacting with our belongings. We cannot live without stuff, we need stuff. I have this beautiful hand-stitched tablecloth from Iran. I might not need it, but it makes me happy to have this piece of textile on my table. The dream is not to not have stuff at all anymore but to have a slower, more thoughtful interaction with the things we do buy, make or get. The dream is that something is so precious that you repair it instead of tossing it.

±

Dye for Fashion

– Interview met Sophie Nelissen en Maike Vierkötter

De textielindustrie is een van de grootste, snelst producerende en meest vervuilende industrieën op de planeet. We verdrinken in kleding en textiel. Maar zijn er ook positieve trends in de industrie? TEMA sprak met Sophie Nelissen en Maike Vierkötter, die zich dagelijks met deze problematiek bezighouden.

Sophie is net begonnen met klein duurzaam modelabel in Maastricht, Nederland. Ze ontwerpt, naait en verft de kleding zelf - meestal met planten die ze in haar achtertuin kweekt. Studio Sufi is geboren uit het verlangen naar een meer verantwoorde manier van mode produceren.

Met een passie voor mode, maar een bewustzijn voor de destructieve impact van de industrie, is Maike momenteel bezig met het afronden van haar Master in Textielindustrie en Toegepaste Duurzaamheid. Daarnaast past ze haar kennis al toe tijdens haar baan in Sustainability Management, waar ze probeert de kwestie van duurzame mode op bedrijfsniveau te krijgen. Voor haar thesis produceerde ze onlangs een zero-waste strandtas, samen met het kledingmerk SALZWASSER, waarbij ze elke stap van de productie overzag terwijl ze de impact op zowel mens als milieu in het oog hield.

Samen spraken we over bewuste modeconsumptie, het verlies van vakmanschap en het benaderen van de productie van kledingstukken vanuit een meer holistisch perspectief.

©lauraknipsael

Viola: Sophie, jouw product proces ziet er heel anders uit dan dat van fast fashion en vakmanschap speelt daar een grote rol in. Kun je ons daar iets over vertellen?

Sophie: Het vakmanschap waar ik het meest in geïnteresseerd ben is het verven. Ik heb toevallig een meisje ontmoet dat heel graag herder wil worden. Haar droom is om uiteindelijk haar eigen kudde schapen te hebben in natuur gebieden. En via haar heb ik een beetje wol in handen gekregen waarmee ik een paar sokken wil gaan maken, gemaakt in Nederland met Nederlandse wol en geverfd met natuurlijke kleurstof die ik zelf kweek, zodat het een volledig lokale en natuurlijke productiekring is. Maar het lastige is dan om het te laten naaien, want in Nederland is het heel moeilijk om mensen te vinden die zelf sokken maken. En de volgende optie, het door mensen met de hand laten breien, is niet haalbaar.

Als je kleinschalig produceert, zoals ik, merk je dat kleinschalig produceren hier duur is, onder andere omdat de productiecycli maximaal geïndustrialiseerd zijn, waardoor grote hoeveelheden nodig zijn, tenzij je je wendt tot klein handwerk. Maar omdat de uurlonen hier over het algemeen duurder zijn, wordt het bijna onbetaalbaar.

Bij merkkleding gaat de consument er vaak van uit dat dit een duur product is en dat het dus wel op een goede manier gemaakt moet zijn, maar dat is vaak niet het geval.

V: Het is geen geheim dat de mode-industrie met heel wat problemen te kampen heeft, zoals die spanning tussen de druk van de markt en de behoefte aan sociaal en ecologisch duurzaam geproduceerde artikelen. Maike heb je ook positieve trends in de industrie waargenomen?

Maike: Ik denk dat het grote bewustzijn voor kwalitatief hoogwaardige en duurzaam geproduceerde kleding langzamerhand weer terugkomt. Dat komt ook door het groeiende bewustzijn van de klimaatverandering. En daar spelen bedrijven op in. Er zijn natuurlijk ook verschillende kleinere labels, zoals Armedangles, dat nu al bijna 12 jaar bestaat, die bewijzen dat je als 'duurzaam' label kunt overleven, ook op lange termijn. Je kunt je natuurlijk afvragen of wat zij doen voldoende is, maar het bewijst in ieder geval dat het kan werken. Bedrijven durven steeds meer duurzaamheid op hun agenda te zetten, betere lonen te betalen en gecertificeerde materialen te gebruiken. Maar ik denk dat het een combinatie is van consumenten die het eisen, bedrijven die het durven aanbieden en moedige, kleinere startups die laten zien dat het werkt.

V: Ik heb altijd moeite om eerlijke en misschien radicale doelen te onderscheiden van greenwashing. Grote bedrijven als H&M brengen 'Consciousness'-lijnen op de markt, maar brengen tegelijkertijd nog steeds 12-16 nieuwe collecties per jaar uit. Dus hoe oprecht en positief zijn deze verschuivingen in de strategieën van grotere modebedrijven eigenlijk?

S: Als conventionele labels natuurlijk geverfde of biologische t-shirts in hun collectie opnemen, of fast fashion merken bewuste collecties maken het geeft je het gevoel dat het ok is om te blijven consumeren zoals we doen. Er is zeker het risico dat we het systeem een klein beetje beter maken en dat we ons dan goed voelen over het handhaven van een betere versie van de status quo. Als we uitzoomen en kijken naar de snelheid waarmee we de planetaire grenzen op alle niveaus overschrijden, beseffen we dat we de status quo helemaal niet kunnen handhaven. Dus ja, je kunt zeggen dat dit een positieve ontwikkeling is, want dit is ook het tempo waarin wij als mensen geneigd zijn te innoveren, en het zal uiteindelijk beter worden. Maar, soms denk ik dat ik maar helemaal geen kleding moet maken, want we hebben al genoeg. Maar we moeten ook vertrouwen houden. Door kleine stapjes te nemen is het makkelijker om moed te houden.

M: Ik ben het helemaal met Sophie eens. Als ik heel eerlijk ben, hebben we zelfs met SALZWASSER een nieuw consumptieproduct geproduceerd dat de wereld niet nodig heeft. Maar het biedt een alternatief voor fast-fashion. Persoonlijk vind ik het heel belangrijk dat ik niemand veroordeel die om financiële redenen bij H&M of Primark gaat shoppen. Dat is volkomen begrijpelijk in deze consumptiemaatschappij waarin wij leven, waarin zoveel draait om oppervlakkigheid en uiterlijk vertoon, dat je bij wilt blijven. Maar als er mensen zijn die 40, 50, 60 euro kunnen en willen uitgeven voor een merkshirt, dan is het belangrijk om bij hen bewustzijn te creëren en een alternatief te bieden via een merk dat een verhaal vertelt.

S: Bij merkkleding gaat de consument er vaak van uit dat dit een duur product is en dat het dus wel op een goede manier gemaakt moet zijn, maar dat is vaak niet het geval. Het zou geweldig zijn als consumenten in deze prijsklasse dat gaan inzien.

Het is deze link met de natuurlijke hulpbronnen, maar ook deze manier van verbonden zijn met de bodem, met de aarde, dat is een heel directe manier om een positieve impact op de planeet te hebben.

V: Wat voor technieken hebben we nodig, anders dan, zoals je zei, storytelling, om consumenten bewuster te maken en hun aankoopbeslissingen te beïnvloeden?

M: Ik denk dat je veel kunt bereiken door onderwijs. Aan sommige universiteiten bestaat het concept "Studium Generale", waarbij iedereen in het eerste semester kennismaakt met verschillende aspecten van duurzaamheid. In verschillende stadia en vormen van onderwijs, zoals middelbare school of beroepsopleiding, word je je bewust van de effecten van je gedrag.

Toen ik textieltechnologie studeerde, was duurzaamheid nooit een onderwerp. Daarom hebben we een initiatief opgezet om dit onderwerp meer in het onderwijs te implementeren. Om de mensen op te leiden die de volgende generatie zijn om in deze industrie te werken. Om ze bewust te maken en te zeggen: "Hé, kijk, als je iets aan het verven bent, zijn er waanzinnig veel chemicaliën in gebruik." Dat besef alleen al zou voor mij genoeg zijn.

V: Sophie, je kwam met zeer specifieke manieren om de problemen aan te pakken die komen met de conventionele manier van verven. Hoe is dat tot stand gekomen?

S: Op een bepaald moment in mijn onderzoek raakte ik gefascineerd door natuurlijke kleurstoffen. De lockdown van vorig jaar gaf me veel tijd om in mijn tuin te werken. Maar de kleuren zijn natuurlijk anders. Vooral op cellulose-vezels, zoals katoen en linnen, zijn de kleuren veel lichter. Maar op bijvoorbeeld wol en zijde krijg je heel heldere, glanzende, mooie kleuren. Een van de redenen waarom ik er zo van houd is deze directe link met natuurlijke bronnen. Net zoals, bijvoorbeeld, een traditionele wilgentenen mandenvlechter de wilg uit zijn tuin gebruikt om een mand te vlechten. Je komt heel dicht bij de oorsprong van het product. Later begon ik meer te leren over nieuwe manieren van landbouw en toen realiseerde ik me dat als je op een betere manier begint te planten, je in feite meer koolstof in de bodem begint op te slaan. Het is deze link met de natuurlijke hulpbronnen, maar ook deze manier van verbonden zijn met de bodem, met de aarde, dat is een heel directe manier om een positieve impact op de planeet te hebben.

V: We hadden het over verandering op een groter niveau, dat er verandering moet komen op het niveau van de productie, maar dat er ook verandering moet komen op het niveau van het consumentengedrag. Maike, een deel van je taak in het duurzaamheids managementteam van de Duitse tassenfabrikant FOND OF is om met verschillende belanghebbenden te praten. Hierbij probeer je een evenwicht te vinden tussen de omvang van het bedrijf en hun commerciële belangen en de duurzaamheidsdoelen die je hebt gesteld. Zijn er problemen die je vaak tegenkomt bij het afwegen van deze belangen?

M: Het bedrijf, en dat geven ze zelf ook toe, is geen duurzaam bedrijf. FONT OF zegt dat we goede producten willen maken, dat we willen groeien en zo duurzaam mogelijk willen zijn. Met drie mensen in mijn team, in een bedrijf met 300 werknemers, zijn we vrij goed gepositioneerd. Maar het is niet vanzelfsprekend dat daar budget voor is, dat we een cradle to cradle rugzak mogen ontwikkelen (Note author: Een ontwerpconcept en certificaat dat een positieve impact heeft op mens en planeet, zonder afval te produceren) of dat we als bedrijf binnenlandse vluchten voor medewerkers verbieden. Het werk van duurzaamheidsmanagement is heel waardevol, want zij initiëren deze gedachten altijd, maar het kost een ongelooflijk lange adem om dingen echt in beweging te krijgen.

Mijn droom zou zijn dat mensen zich meer bewust worden van wat er achter deze producten zit en dan bewuste consumptie beslissingen nemen.

V: Maar kunnen grote mode- en textiel bedrijven eigenlijk wel 'duurzaam' zijn?

M: Als ze dat echt willen, ja. Maar de andere grote vraag is: willen we überhaupt wel meer consumeren? Als je zegt dat we, vooral in de fast fashion, toch al te veel consumeren, dan is dat zelfs als we 100% gerecycleerde materialen zouden nemen en 100% natuurlijke kleurstoffen zouden gebruiken, nog te veel.

S: Ik denk dat je punt van overconsumptie waar is. Dit gaat weer terug naar de discussie over in hoeverre we de status quo willen uitdagen. Het is heel moeilijk om radicale veranderingen door te voeren.

V: Wat radicale veranderingen betreft, als je een droom had voor de mode-industrie en -consumptie voor de toekomst, wat zou die dan zijn?

M: Ik hou van mode. Ik vind het leuk dat je er iets mee kunt uitdrukken. Mijn droom zou zijn dat mensen zich meer bewust worden van wat er achter deze producten zit en dan bewuste consumptie beslissingen nemen.

S: Daarop voortbordurend, als iedereen zo'n bewustzijn zou hebben, zouden we op een andere manier met onze bezittingen omgaan. We kunnen niet zonder spullen leven, we hebben spullen nodig. Ik heb dit prachtige handgestikte tafelkleed uit Iran. Ik heb het misschien niet nodig, maar het maakt me blij om dit stuk textiel op mijn tafel te hebben. De droom is niet om helemaal geen spullen meer te hebben, maar om langzamer, bedachtzamer om te gaan met de dingen die we wel kopen, maken of krijgen. De droom is dat iets zo waardevol is dat je het repareert in plaats van het weg te gooien.